In June 2020, partly in reaction to the COVID fiasco, General Michael Flynn made the following famous quote:

“[I]f we’re not careful, 2 percent of the passionate will control 98 percent of the indifferent 100 percent of the time.”

The quote hints that up to 2% of us might turn out to be irredeemable control-freaks, hell-bent on slave-driving other people into oblivion. If held to be the truth, can we succeed as human beings when 2% of us will persistently “refuse to play nice?” The question has never, ever been as important, but early philosophers had the answer.

The title of this piece uses the word “evil” in a very loose manner to refer to any level of mischief which some human beings become willing to put other human beings through — in order to profit off of the hardship of others.

Hard Times Don’t Need Explaining

Anyone who has watched a cheetah run down a gazelle on the Discovery Channel or Animal Planet should know that hard times are to be expected, and that they do not need an explanation. Life can be cut-throat. But more importantly, life — and even successful peace and prosperity — can be achieved without being cut-throat.

Why have there been good times?

If hard times are so expected that they do not even need an explanation, then how is it that there have been good times? Early philosophers pointed out how it is that human beings are very special creatures who can agree to work together for a better life. While some colony insects like ants and bees also work together, it is different for us.

When the USA was set up, it was set up on the notion that humans like to work together, but that interests can still diverge and factions can spring up and loyalties can break down and, if you don’t plan ahead, it can all end in a shambles. Here is Federalist No. 51 [emphasis added]:

But the great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department, consists in giving to those who administer each department the necessary constitutional means and personal motives to resist encroachments of the others. The provision for defense must in this, as in all other cases, be made commensurate to the danger of attack. Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government.

So the reason that good times are possible — even if a minority of us will not ever be willing to “play nice” — is that you can outsmart evil, or at least plan ahead for it. By splitting government into branches horizontally, and into federal, state, and local vertically, the U.S. was set up to succeed even if 2% of people will not ever “play nice.”

It was a government set up so that it could withstand evil, and society could still flourish in spite of the fact that not everyone plays nice. And flourish we did!

In Game of Thrones, Ned Stark says this:

The reason to inculcate this principle is so that dastardly people who obtain power are forced to personally deal with the blowback of exercising that power, which helps to keep them from abusing it. Even in things so simple as dividing up that last part of a pie, you can use the following rule with an expectation of a 100% success rate:

I cut, you pick.

Notice how that rule is “fool-proof” and how it cannot be “gamed” by a con man. Once adopted, there is no chance for an overly-greedy person to get ahead by stepping on the rights of others. Whether they end up cutting or picking, you both end up with half — always.

The only thing to remember when making the rules is that a minority of people do not play nice. Once that is thoroughly incorporated into rule making, good rules follow. The first question when contemplating new law should not be: Can good come from this? The first question when contemplating new law should be:

Can bad come from this?

If the law can get misused (by that 2% of people who we can count on to attempt to misuse it) then don’t pass it.

Power Dynamics

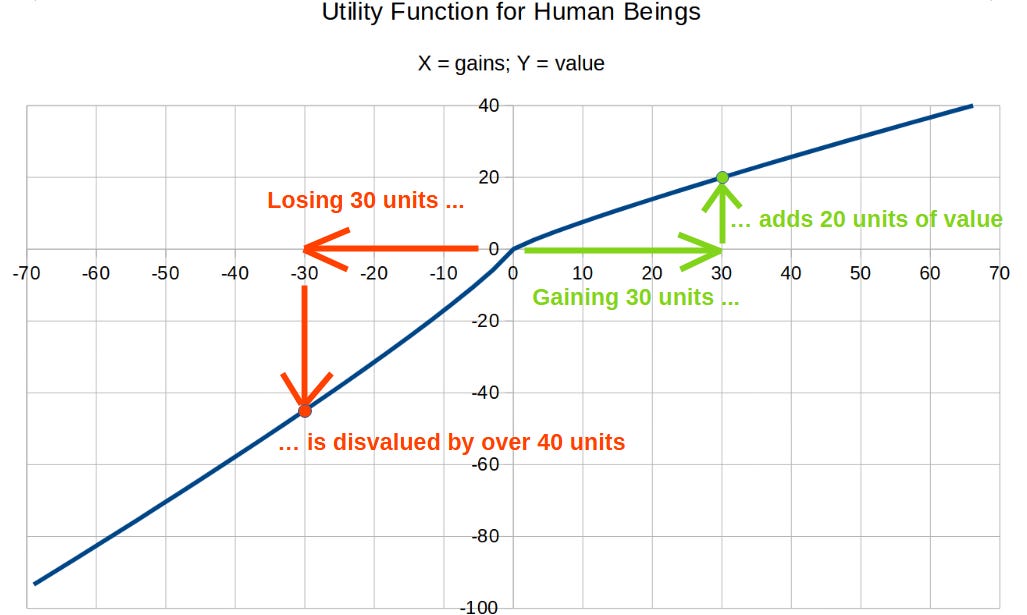

Ever wonder how it is so often the case that someone uses free market capitalism to get ahead, only to then turn around and work against freedom? This graph explains it:

Initially getting rich gives people subjective value, but once rich, losing some of your riches causes much more pain than gaining it caused joy. Because of this situation where losses “hurt you more” than your prior gains ever helped, rich oligarchs often turn against society. They used a ladder of success, and then they pull up the ladder.

This is done so as to permanently enshrine themselves as oligarchs. By preventing the rise of others, they gain insurance of what they covet: holding onto what they have. The achieved level of riches does not matter like you think it would, and any losses are abhorred. Billionaires could cry, or act out against others, over a single lost dollar.

But, because you can plan ahead for the attempted control they eventually seek, you can prevent it — with the right rules and principles. The multiplier on the weight placed on losses in proportion to that placed on gains can even reach up to six!:

For groups of people represented by the dots at the right, losses hurt them by so much that they hurt them by 6 times more than the initial joy of gain. If such a person got rich and their riches were put into jeopardy by economic competition, then they might become willing to engage in “extra-legal” action to remove competition.

But, because you can plan ahead for the attempted control they eventually seek, you can prevent it — with the right rules and principles. Our Founding Fathers got almost everything right when they first set up the founding documents of the United States of America:

—The Declaration of Independence

—The U.S. Constitution

—The Bill of Rights

Prior to the time of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, John Adams had written a letter to Patrick Henry, mentioning factions and how they can tear the country apart, but how you can plan ahead for the attempted control they eventually seek, producing “a more equal Liberty, than has prevail’d in other Parts of the Earth”:

The Dons, the Bashaws, the Grandees, the Patricians, the Sachems, the Nabobs, call them by what Name you please, Sigh, and groan, and frett, and Sometimes Stamp, and foam, and curse—but all in vain. The Decree is gone forth, and it cannot be recalled, that a more equal Liberty, than has prevail’d in other Parts of the Earth, must be established in America. That Exuberance of Pride, which has produced an insolent Domination, in a few, a very few oppulent, monopolizing Families, will be brought down nearer to the Confines of Reason and Moderation, than they have been used.

When making the choice between furthering a surveillance state, or a bio-medical security state, we have to remember that — because 2% do not play nice — we need to prevent the peculiar power asymmetry that comes with those in charge of surveillance or of social credit scores or of central bank digital currencies.

Call it the “Flynn Rule.”

Because 2% won’t ever become willing to play nice, we cannot allow for bureaucracy to grow to the point that it has information and control over individual persons. We have to roll back what has already been done. Peace, prosperity and domestic surveillance cannot all coexist.

Secret police cannot continue to be allowed inside of the USA.

"Secrecy is the beginning of tyranny." — Robert A. Heinlein

Reference

[Federalist No. 51] — https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed51.asp

[Ned Stark quotes] — https://screenrant.com/game-of-thrones-ned-stark-quotes/

[Letter from John Adams to Patrick Henry, 3 June 1776] — https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-04-02-0102

[The essay that sparked the “Flynn Rule”] — https://www.westernjournal.com/exclusive-gen-flynn-dont-act-2-people-control-98/

[2.7% of people (“spiteful competitors”) will not play nice, but we can make rules for them] — Brañas-Garza P, Espín AM, Exadaktylos F, Herrmann B. Fair and unfair punishers coexist in the Ultimatum Game. Sci Rep. 2014 Aug 12;4:6025. doi: 10.1038/srep06025. PMID: 25113502; PMCID: PMC4129421. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4129421/

[losses personally weighted up to 6 times what gains were weighted] — Brown, Alexander L., Taisuke Imai, Ferdinand M. Vieider, and Colin F. Camerer. 2024. "Meta-analysis of Empirical Estimates of Loss Aversion." Journal of Economic Literature, 62 (2): 485–516. DOI: 10.1257/jel.20221698. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.20221698 Also in full: https://www.taisukeimai.com/api/resources/loss_aversion_meta.pdf