Why not Anarchy?

Post #1385

NOTE: An earlier post related to this one is here.

One of the most intelligent economists to ever live, Murray Rothbard, was an anarchist. Acknowledging how correct Murray Rothbard was on almost everything makes the title of this piece seem awkward. A subtitle could have been “Murray Rothbard’s blindspot.” On the international stage, anarchy really is for the best.

It is the situation of a “state-of-nature” wherein no entity reigns supreme.

But when inside the geographic boundaries of a nation, it will be argued that minarchy (having a government large enough to enforce the law) is best. If people were all so rational that they did not suffer from loss aversion and from spiteful competition, then anarchy would work out well for human beings.

It is likely that Murray Rothbard thought all people could get there (become rational).

But as luck would have it, not all people are capable — even after instruction and correction — of reaching an impartial state of perfect rationality. It’s just too high of a bar for us all to meet.

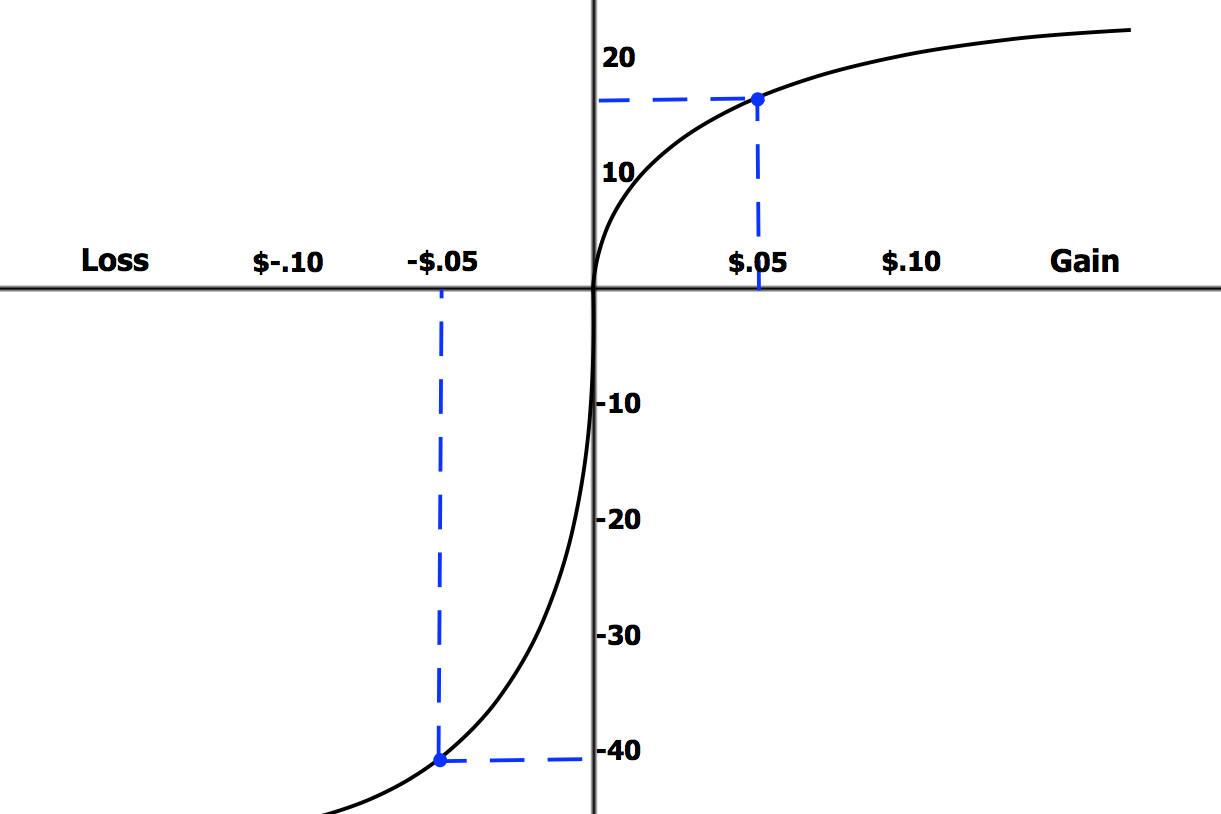

Loss Aversion

Loss aversion is the “irrational” valuation of losses at a level that is higher than your gains, and many people “suffer” from it. If you gain a nickel, it might provide you with almost 20 hypothetical units of utility or satisfaction, but if you lost a nickel, it could provide you with over 40 of those same units in disutility or dissatisfaction:

This phenomenon of “hyper-valuation” of losses compared to gains can lead to problems when attempting to operate under pure anarchy. Once an ambitious member of society utilizes the free market to gain things, then they have an outsized incentive to turn against the free market in order to lock-in their gains.

Borrowing a phrase from Schumpeter, they will then seek to thwart “creative destruction” (the process whereby stale or outworn production processes are supplanted by innovative methods of producing value). It is just at that moment when they have more resources than average, that they have such a power and an incentive.

Spiteful Competition

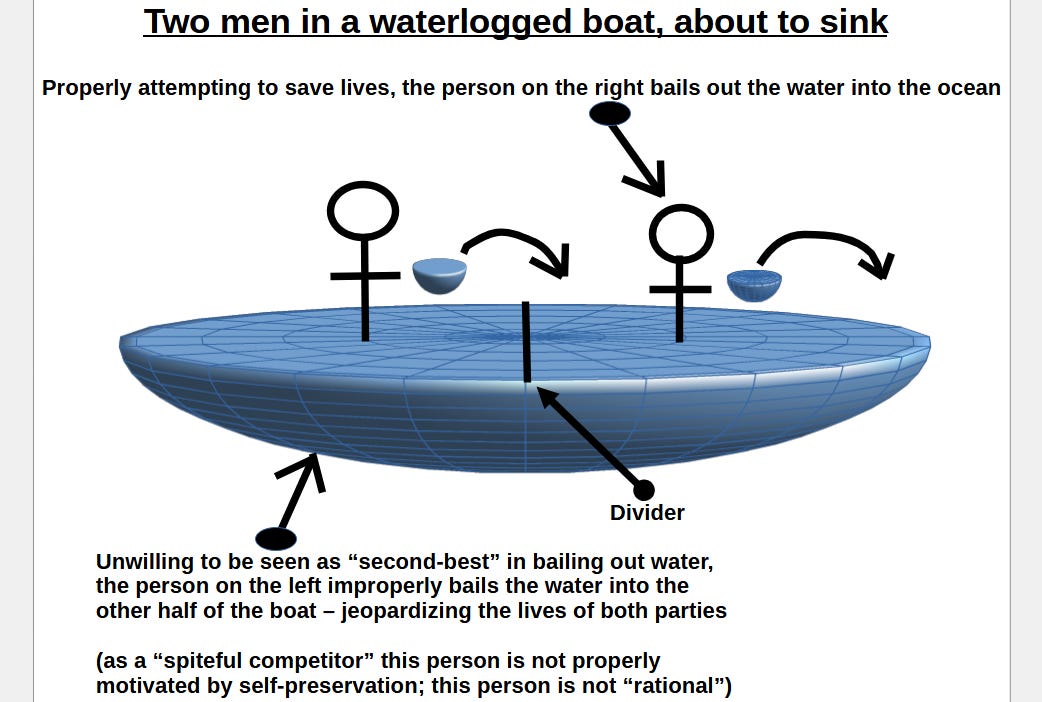

Each generation, approximately 2% of humanity has a “defect” which prevents them from the attainment of a full and impartial rationality. What is true for 98% of us is not true for that last 2% of us. Spiteful competitors cannot become satisfied with winning or with building a better life for themselves.

For them, the other guys (their opponents) must also lose.

Picture two men in a sinking lifeboat, each outwardly agreeing to help bail out the water, so that they won’t both drown:

While there is great comfort that less than 3% of humanity will be found to be spiteful competitors, even having 1% of people act that way undercuts the ability of anarchy to be a good social system for humankind. Anarchy, in theory, depends on people being capable of learning their way out of harm. The markets will teach them this.

But a spiteful competitor is not primarily interested in gaining objective success in the world, they are only interested in relative success — i.e., they do not necessarily feel any better when they are better off, but only when you are worse off, as well. Being above or beyond you is what is important to them. It is of top importance.

They are unable to be happy when everyone is equally better off than before.

The phenomenon of Loss Aversion, as well as the more rare phenomenon of Spiteful Competition, make it so that — inside of a nation’s borders — there needs to be an objective and transparent rule of law which is enforced by an impartial third-party (i.e., a government). This allows men to settle differences with words, not violence.

Reference

[2.7% of people (“spiteful competitors”) will not play nice, but we can make rules for them] — Brañas-Garza P, Espín AM, Exadaktylos F, Herrmann B. Fair and unfair punishers coexist in the Ultimatum Game. Sci Rep. 2014 Aug 12;4:6025. doi: 10.1038/srep06025. PMID: 25113502; PMCID: PMC4129421. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4129421/

[losses personally weighted up to 6 times what gains were weighted] — Brown, Alexander L., Taisuke Imai, Ferdinand M. Vieider, and Colin F. Camerer. 2024. “Meta-analysis of Empirical Estimates of Loss Aversion.” Journal of Economic Literature, 62 (2): 485–516. DOI: 10.1257/jel.20221698. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.20221698 Also in full: https://www.taisukeimai.com/api/resources/loss_aversion_meta.pdf